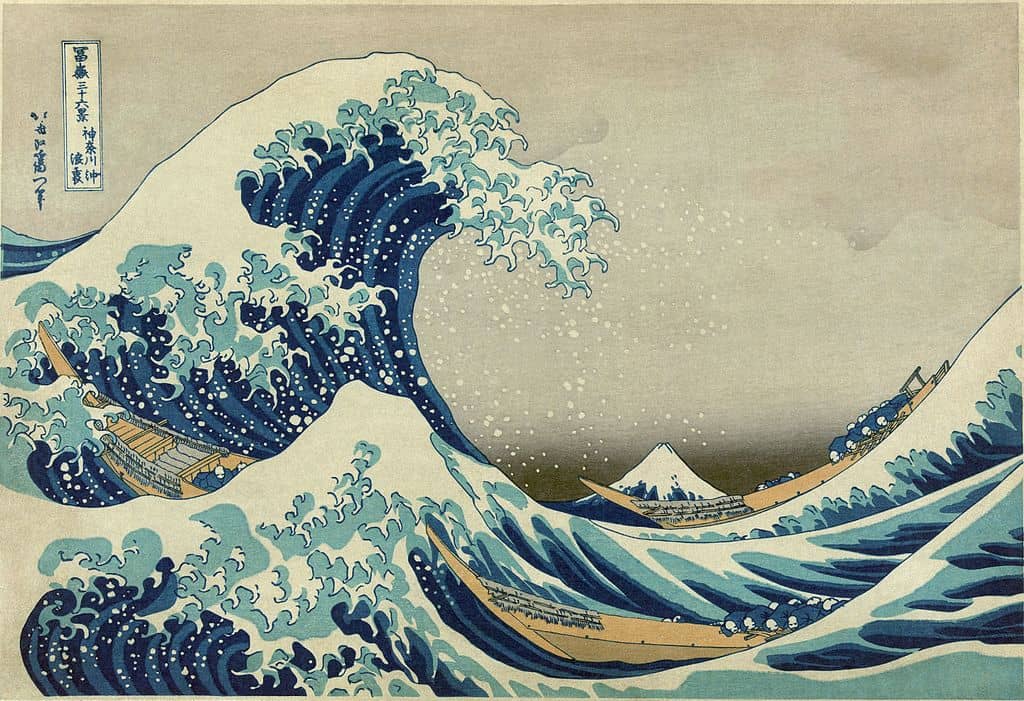

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is probably Japan’s most famous artist. His The Great Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki namiura) is one of the most enduring images of Japanese art. It’s the one that springs to most minds in any discussion of Japanese art.

It is, in fact, a woodblock print, and the first of 36 Views of Mount Fuji, (though in his lifetime, he made 46). Most often the wave is reproduced because the shape of the waves looks a lot like hands reaching out to the land. Mount Fuji is in the lower third of the painting to the right. And yes, the area around Mount Fuji is where the apples originated. Its actual size is the standard ōban size of 25 cm high by 37 cm wide – quite a small picture for such a large impact.

The complete picture also includes three fishing boats, and

But back to Prussian Blue. According to Hugh Davies, the colour came about by accident around 1705 when Swiss pigment maker Johann Jacob Diesbach was attempting to produce a dark red in his Berlin lab and used a tool tainted by one of his lab partner’s experiments. (Fascinatingly, the lab partner, Johann Conrad Dippel was attempting to create an immortality serum when he created an insect repellent so toxic it was weaponised in World War II).

It was an immensely profitable discovery, as a similar blue effect could only be produced with crushed lapis lazuli, and you can’t blend it to create other colours. Europe went mad for it, and it became popular in wallpapers, fabrics, and most notably Prussian Army uniforms (thus Prussian Blue).

An enterprising Chinese resident began manufacturing it in the early 1800s, from where it evaded Japanese import bans and gained popularity as Berlin Blue. The Japanese went mad for it too, and Hokusai among others pioneered its use. The prints were not embraced by the cultural elite so that when American Matthew Calbraith Perry and his warships forced Japan to open for international trade in 1853 they were used as wrapping paper. Up until the Paris Exposition of 1867 at any rate when they became popular for themselves. Especially, you guessed it, the blue ones.

Hokusai wasn’t just fascinated by the colour, but by European art as well, and experimented with the Western style of painting. You can see this in the Great Wave where Mt Fuji is in the background at the vanishing point but is actually the focus of the picture (views of Mt Fuji). If he had created this image in the traditional Japanese style, Mt Fuji would have been the biggest element because it is the most important. This is one of the key reasons we love his pictures so much; because we understand them.

Hokusai’s street life prints inspired Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The Japanse aesthetic was Monet’s inspiration for his Giverny gardens. And of course, Van Goch painted Starry Night – both the colour and the shape of the clouds inspired by the wave.

The National Gallery of Victoria has five of the 36 prints (including The Wave) and these are on display along with 176 others (including the full Mt Fuji series) from the Japanese Ukiyo-e Museum, Matsumoto until 15 October 2017. I urge you to visit as these are some of the most significant pieces of transitional art you’re likely to see.

If you can’t get here for the exhibition, Hokusai’s work is also at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Claude Monet’s home in Giverny. You’ll want to check they are on display before you visit!